what makes a fabulous period wardrobe?

a dialogue on the period-accurate rulebook and how it's articulated, reimagined and (mindfully) thrown out the window by our favourite frock flicks 🎀

Amid the haunting and somewhat off-kilter opulence of The Favourite, Emma Stone struts across the screen in a parade of outfits that wouldn’t have been seen in an 18th century court.

Traipsing through the woods in recycled denim and decked out in studs at court, the titular Favourite’s costumes are infused with a punk spirit which speak more to her personal journey than to any strict historical accuracy. And while the costumes certainly entertain, they also serve as intricate tapestries of personal and political tension, communicating power, manipulation, and rebellion without uttering a word. In this world, the women are chess pieces, their every move dictated by rules—their monochromatic ensembles a silent metaphor for that control.

This balance of exuberance and intention is what fashion historian Judith Watt describes as “serious frivolity”. As we discuss period costuming over the phone, I latch on to her every word—she oozes excitement and sparks curiosity in every subject she touches on—but this phrase in particular sticks to me.

As the conversation progresses, I come to catch her meaning. Fantastic period costuming must be anchored in research, research, research—and then it calls for clever creativity and imagination which visually communicate character and drama within the narrative. As it goes for everything else in life, one must know the rules in order to break them.

And in the field of historical dress, the rules are never-ending. Period costumiers bear the task of combing through books, historical archives, paintings and photographs in order to understand every stitch and thread. Every last detail is important, whether it is on-screen or not.

Luchino Visconti’s Palme D’or-winning 1963 adaptation of The Leopard (Il Gattopardo) exemplified the all-consuming effects of compelling costume design. Costumier Piero Tosi shared Visconti’s own obsession with historical accuracy, and the two collaborated on many of Visconti’s films. But The Leopard stands out for its ornamental exuberance and the wealth of textures involved, creating a delightfully visceral experience which transports viewers to the final days of the Sicilian principality.

Tosi insisted on complete accuracy in every detail—Hamish Bowles noted for Vogue in 2019 that this extended even to items hidden from the camera, like a lace handkerchief tucked into a purse or a pair of underwear in a closed drawer. This extensive use of unseen antique objects may not have been visible to the naked eye, but it is certainly felt through the screen via the actors, whose imaginations had been whisked back to 19th century Italy through this meticulously-crafted set.

Yet even when a film does not strive for Tosi’s level of pristine period accuracy, research is vital. Academy Award-winning costume designer Alexandra Byrne (Elizabeth, Mary Queen of Scots, among others) stresses this in an interview with The Costume Designers’ Guild. “Research is crucially important, whether you’re going to be accurate or not,” she says, reflecting on her illustrious career. “My job is to tell a story… I think sometimes to be overly-bound in period accuracy is a red herring. You need to be free to make good design decisions.”

Costume designer Andrea Flesch (Colette, Midsommar) happily recounts her time poring over archives to craft her extensive resumé of historical wardrobes. “Historical costumes are never boring. I always find something new—I could do the same time period 10 times and never get bored,” she tells me, sheepishly admitting that she does not feel the same way about contemporary costumes.

Rigour is apparent throughout Flesch’s oeuvre. For Colette, she was determined to use as many original antique garments as possible, in order to create a world that felt real and inhabitable. She ended up sourcing over 100, spending six months alone scouring the Internet for the exact pieces she envisioned.

When asked about the importance of authenticity, Flesch talks about the importance of the feel on set—regardless of whether audiences pick up on it. We go off on a tangent from period costuming for a moment, and I asked about her decision to source century-old linen from across Eastern Europe to dress the Swedish cult in Midsommar. She gushes about how vintage fabrics have a certain integrity and quality contemporary ones simply cannot possess. It feels different, she decides.

“Do you think audiences can tell the difference?”

“I don’t know if they can,” she says, after a moment of deliberation. “But in my heart I can see the difference, I think it adds to the visuals of the entire movie.”

Yet, choosing to use original pieces does not mean that there is no room for creativity. Colette tells the story of celebrated French author Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, who penned the Claudine novels at the turn of the 20th century (her novel Gigi would become adapted into the winner of 1958’s Best Picture award). Starring Keira Knightley as the intelligent, sensual and defiant literary icon, the film charts her winding path from country girl to one of the most renowned writers of France. A symbol of female empowerment still relevant in today’s social landscape, Flesch imagined Colette as a dynamic, modern woman.

“I imagined her [to be] a bit like Coco Chanel,” Flesch says, taking notes from the two Parisian women’s mutual admiration and friendship in the early 20th century.

Knightley was dressed in a clean, fresh colour palette composed of ivory, navy and pastels that is still extremely chic today. Her lines are sleek and elegant, even when sporting period-appropriate mutton sleeves and cascades of ruffles. As she morphs from being her husband’s ghost writer to a literary legend in her own right, her outfits become increasingly masculine and she grows a penchant for fitted blazers and bowties.

“I don’t know if I would do it again,” Flesch admits lightheartedly, recalling the tedious process. But the end result proves worthy—it is a paragon of Watt’s serious frivolity, combining both attention to period-accurate detail and intentional innovation. Colette is also Flesch’s most personally treasured work. “I’m the most proud of that film… I think it came out beautifully.”

Though she is no novice to the corset, Knightley escaped the contentious garment for this film. While the real Colette would have worn them at least from time to time, this is another area in which character development trumped historical accuracy.

“Colette was so ahead of her time, so [the corset] was not something which would have suited her character,” Flesch justified. The decision to leave the form-fitting piece out of the film entirely reflected the titular character’s fight for emancipation and personal autonomy. It also allowed Knightley to move freely and embody the physicality of a woman uninhibited by society’s expectations.

It is almost comical how much debate the corset stirs up in any historical or historical-adjacent piece of media. Emma Watson’s decision to ditch the garment in Beauty and the Beast garnered more press than, arguably, the film itself. Critics at the time pounced at the outlandishness of a woman in Baroque-era France going corset-free—which is slightly absurd when you consider the film’s primary love interest is a monster who magically transforms into a prince in its conclusion.

Perhaps it is the corset’s inextricable correlation with society’s expectations of female restraint which make it so significant. The image of Kate Winslet tightly being strapped into a particularly constricting corset likely speaks volumes about her entrapment in a gilded cage, more than words ever could. By the time Titanic begins its descent, she trades the tight-laced finery for a light chiffon gown which billows behind her as she runs away with Jack, finally breaking free from her old life.

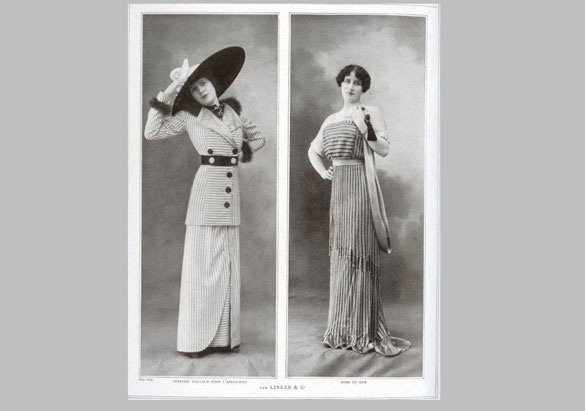

Serious frivolity, in Titanic, grounds fictional characters in real-life tragedy. Rose’s striped ensemble while boarding the ship is a design which appeared in Parisian fashion magazine Les Modes in April 1912. Such intentionality, though not immediately noticeable to audiences unfamiliar with century-old periodicals, gives Jack and Rose a certain tactile quality, which allows us for a moment around the three-hour mark to forget that the star-crossed lovers did not really exist on the sunken vessel.

When asked for her opinions on how important historical accuracy should be, Watt said matter-of-factly, “it depends on what the film is trying to be.”

Elizabeth: The Golden Age is steeped in regal grandeur and dramatic intensity. It sees Cate Blanchett’s rendition of the Virgin Queen transcend into divinity amid political strife and instability. Alexandra Byrne’s Oscar-winning costume design tracks this ascent. Her Elizabeth is clad in lavish gowns that use the queen’s real-life wardrobe as a blueprint, and count Cristobál Balenciaga’s designs from the 1950s among the contemporary influences on her moodboard. Call it upcycled Tudor couture which borders on ethereal.

Its Oscar win in the Best Costume Design category was, as writer Liz Hoggard puts it in a 2007 essay, “supreme vindication”—referring to the film’s detractors who widely condemned its narrative choices. In her advocacy for the film’s costuming, she echoes Watt’s sentiments. “Clothes in cinema are not just frivolous. Sometimes the fantasies they inspire are sheer escapism, but at others they’re inspirational, even subversive.”

In the case of Marie Antoinette, Sofia Coppola and Milena Cananero turned 18th-century fashion on its head. Crafting an exuberant bubblegum-punk aesthetic fit for the coquettish young Dauphine, the anachronistic outfits speak to her youthful naïveté within the gilded cage of Versailles.

The iconic I Want Candy scene features a swoon-worthy confection of Manolo Blahnik creations, in every shape and colour imaginable and decorated with exquisite gems and flirty frills. Manolos had become the coveted It-shoe of the 2000s—Marie Antoinette was released two years post-Sex and the City’s original run—how better to convey a sense of enviable excess to a modern audience?

Though it opened to moderate success at the box office, Coppola’s film has gained recognition over the years for its distinctly playful style, feminist lens and empathetic portrait of the divisive queen. Kirsten Dunst, who plays the titular teen queen, could not have said it better when she said that the film is a “history of feelings rather than a history of facts.”

Such tongue-in-cheek ahistoricism, as it turns out, has proven to be great fun. Perhaps Marie Antoinette would have been better received if it had been made two decades later, released to a public better versed in anachronistic storytelling.

Ahistoricism has been gaining momentum in recent years, emerging as a bold and playful trend that challenges historical boundaries and celebrates timeless creativity. Such otherworldly representations of the past often stir heated debate—some love it, some loathe it—but it makes for entertainment that continues long after the final scene.

“There is a wider trend for ahistoricism in period films,” Lauren Cochrane, senior fashion editor at The Guardian, writes to me in an email. “I guess it’s about providing a surprising juxtaposition and also to engage audiences who wouldn’t typically be interested in these kinds of stories.”

Years after Marie Antoinette, Autumn de Wilde’s adaptation of Jane Austen’s classic Emma would take inspiration from the former’s stylistic sensibilities, but with much greater praise from critics and the public. Production designer Kave Quinn told Variety in 2020 that de Wilde specifically wanted to draw on the pastels and lightness of Coppola’s film. Alexandra Byrne took cues from this and designed a wardrobe which exaggerated class discrepancies in an almost comical and absurd way. The actors were draped in over-the-top bows and necklaces to accentuate the humour and social commentary.

Netflix’s Bridgerton remains a conversation starter for its playful disregard for historical accuracy, tossing the rulebook out the window and opting instead to reimagine the Regency with contemporary and fantastical touches. Complete with orchestral covers of pop anthems fresh off of Spotify’s Hot Hits playlist, Shonda Rhimes’s alternative history is decidedly (and unapologetically) a fluffy rom-com pastiche of social life in Queen Charlotte’s court, complete with operatic and flamboyant outfits to match.

Bridgerton’s costume designer for season one Ellen Mirojnick (Oppenheimer, The Greatest Showman, Fatal Attraction) sets the tone. Apart from studying drawings and paintings of London in the early 19th century, she turned to modern inspirations, citing the V&A Museum’s Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams exhibition as a key contributor. In an interview with Vogue back in 2020, she divulged the tantalising details behind the show’s strikingly decadent aesthetic.

“We wanted to experiment with it by layering on other fabrics and embellishment. Using either organza, organdy or tulle, we could create another layer on top of the dresses that gives it a new sense of movement and fluidity,” she explains. In a bid to create something more aspirational than realistic, some period-accurate elements were banned: visage-shielding bonnets were outcast. “Another no-no was muslin dresses. There’s a limpness to them that we didn’t want.”

That being said, ahistoricism isn’t confined to dizzying escapades. In Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Emma Corrin graces the screen as the titular lady in outfits you could probably recreate via a trip to your local Reformation or Sézane. The clothes in this adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s provocative 1928 novel feel undoubtedly classic and of a bygone époque, yet there is a contemporary sensibility to them more visually cohesive with themes of class-defying romance and sexual liberation.

Lady Chatterley’s costume designer Emma Fryer is no stranger to the concept of ahistoricism, counting satirical dark comedy The Great and alternative historical rom-com Shakespeare in Love among her well-known projects. For D.H. Lawrence’s heroine, she looked to contemporary luxury womenswear brands like Needle & Thread and Zimmermann for inspiration. The result of a period wardrobe off the high street? An effortlessly chic heroine with whom modern audiences identify and sympathise—one who also inspires a serious urge to hit the shops.

It won’t be the first time film costumes have sparked fashion revolutions off-screen, Cochrane notes as we discuss trends. With the increasing accessibility of fast fashion and e-commerce, trends come and go in the blink of an eye, and audiences typically seek to cosplay the characters who most capture their imagination. See: Challengers and tenniscore, Euphoria and the Y2K resurgence, and more recently A Complete Unknown coincides with the boho-chic revival. Yet, such seemingly fleeting moments are still born out of a deliberate attention to style. “I think these stand out because they are consciously stylish, they are aware of creating an aesthetic impact,” observes Cochrane.

At the heart of it all, costume design in period pieces is not just about replicating the past—it’s about telling effective stories that connect with viewers.

As the lines between history and fantasy continue to blur, particularly in the world of ahistoricism, these costumes become more than just garments; they are metaphors for empowerment, rebellion, and the complex role of women throughout history. Whether it’s through the subversive stylings of Marie Antoinette or the liberating blazers of Colette, the serious frivolity of period costuming is a way to reframe our understanding of the past. It's an art that invites us to question, to imagine, and to see history through a different lens—one that allows for both creativity and insight to coexist.

“I’m not making a documentary,” Flesch laughs, as she talks about receiving the occasional critique for taking creative liberties with period dress. “I don’t think you always have to stick to the rules… you can create amazing things every day.”

At the end of the day, what makes a fabulous period wardrobe?

“Knowing [the historical context], taste,” Flesch laughs humbly as she adds, “and talent.”

The day after my phone call with Watt, I was delighted to awaken to an email from her containing her closing thoughts, and urging me to watch the Netflix remake of The Leopard that just dropped last week. I reach for my pen again to scribble down the sentence I would use to close this piece. “The costume designer is meant to communicate character… and drama!” Watt concludes.

I watched the Leopard last night after reading this. I had never heard of it so I figured I would give it a shot.

It was visually gorgeous and then there was the whole plot line of the movie! It was an absolute treat. I am so glad I found it through this. Thank you so much for turning me into it!